By Eve Davidian and Oliver Höner

Why is it that in some species individuals are more willing to help their groupmates than in other species and why does the willingness to help change with age? In our new study led by colleagues from the University of Exeter and just out in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution, we shed light on the possible roots of differences in willingness to help others across animal societies and between individuals of different age and sex. Using data from seven mammal species – including spotted hyenas – we show that the number of kin an individual has in a group can change over its lifetime. These ‘kinship dynamics’ often differ between males and females and profoundly influence the incentive of individuals to help their groupmates.

When you live in a group of close kin, it might be in your best interest to help your groupmates because helping individuals who share genes with you such as your offspring and siblings is a bit like helping yourself. In contrast, when you live among distantly-related or unrelated individuals – say, second-degree cousins or total strangers – your best strategy may be to be selfish or even harmful to the others. But what happens when the number of kin in a social group fluctuates over time, for example because some family members disperse or die? To answer this question and get an idea of what is going on across mammals, we teamed up with scientists working on other awesome animals: the killer whale, yellow baboon, banded mongoose, chimpanzee, rhesus macaque, and European badger.

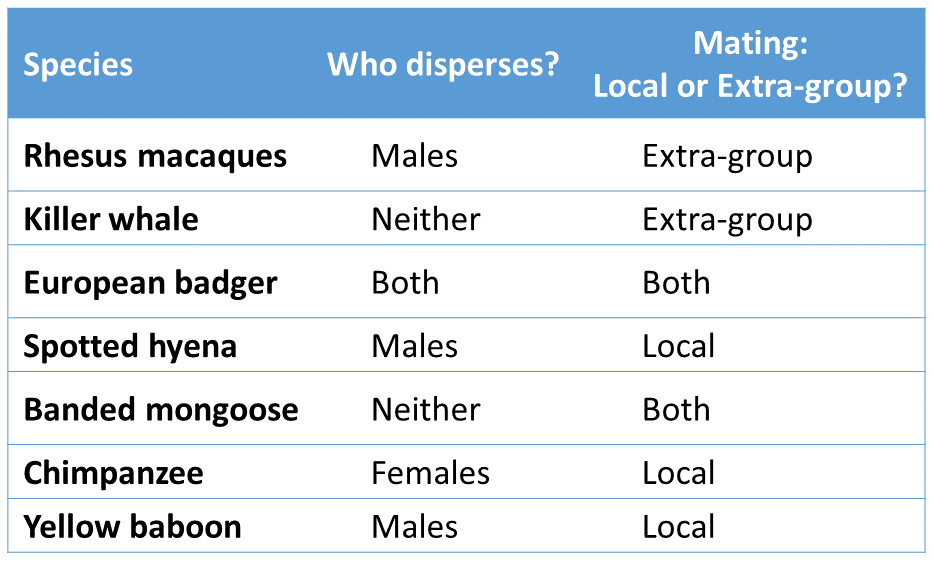

The seven species were not picked at random. Our Exonian colleagues looked for the “crème de la crème” of wildlife datasets. This means species for which scientists compiled a detailed genetic pedigree (aka ‘family tree’) of a population and demographic information over the lifetime of many individuals of the population. To give you an idea, the hyena dataset used for this study contained data on the life history – i.e., the birth, reproduction and death – of more than 2000 spotted hyenas over nine generations. This required 26 years of continuous monitoring (see how we do) of our eight study clans in the Ngorongoro Crater. And it was crucial for the study that the species differed from one another in two key features of their social system:

- Dispersal: Are some individuals (males, females, both, neither) more likely to leave their birth group when adult?

- Mating: Do individuals reproduce with members of their own group (‘local’ mating) or mainly seek mates in other groups (‘extra-group’ mating)?

Dispersal and mating patterns shape kinship dynamics. We found that the number of kin an individual has in a group changes over its lifetime but also that the direction of the change – that is, whether it increases or decreases – is determined by the species dispersal and mating patterns. As a result, kinship dynamics vary from species to species but patterns also often differ between males and females of the same species.

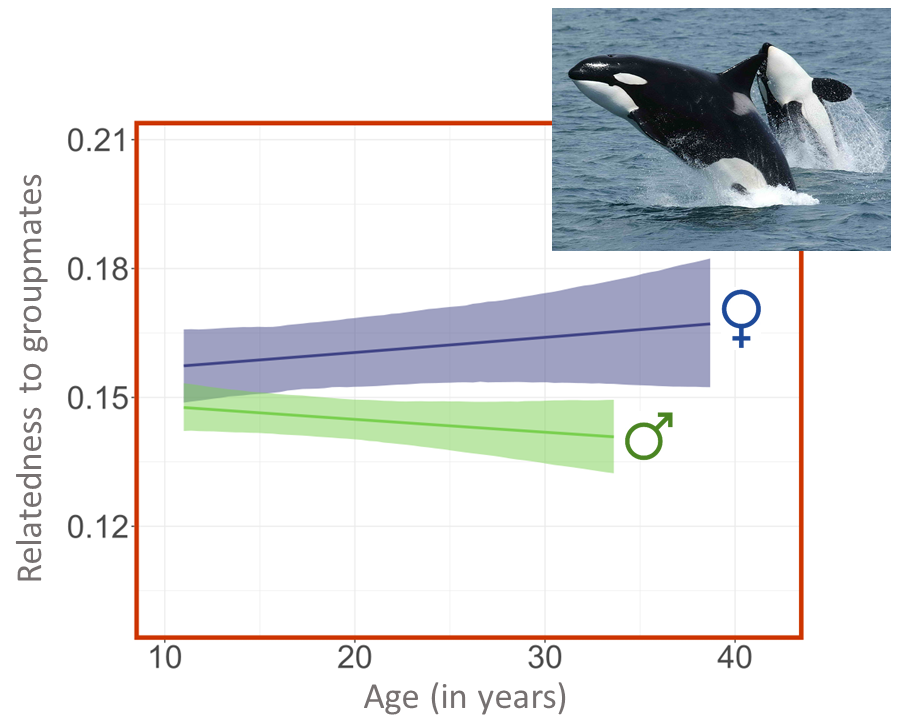

Kinship dynamics may explain why female killer whales go through menopause. In killer whales, neither sex disperses from their birth group (called a ‘pod’). Sons and daughters thereby both remain with their mother and adult females live among a growing number of offspring and grand-offspring as they age. This pattern was suggested to explain why old female killer whales – and possibly also women in humans – experience menopause as a ‘cooperative’ strategy to avoid the costs of competing with their daughters and grand-offspring (see study here). For male killer whales, patterns are reversed because of the “extra-group” mating system, which implies that males sire offspring with females that live in other pods. As a result, the offspring that are recruited in their pod are not closely related to the native males.

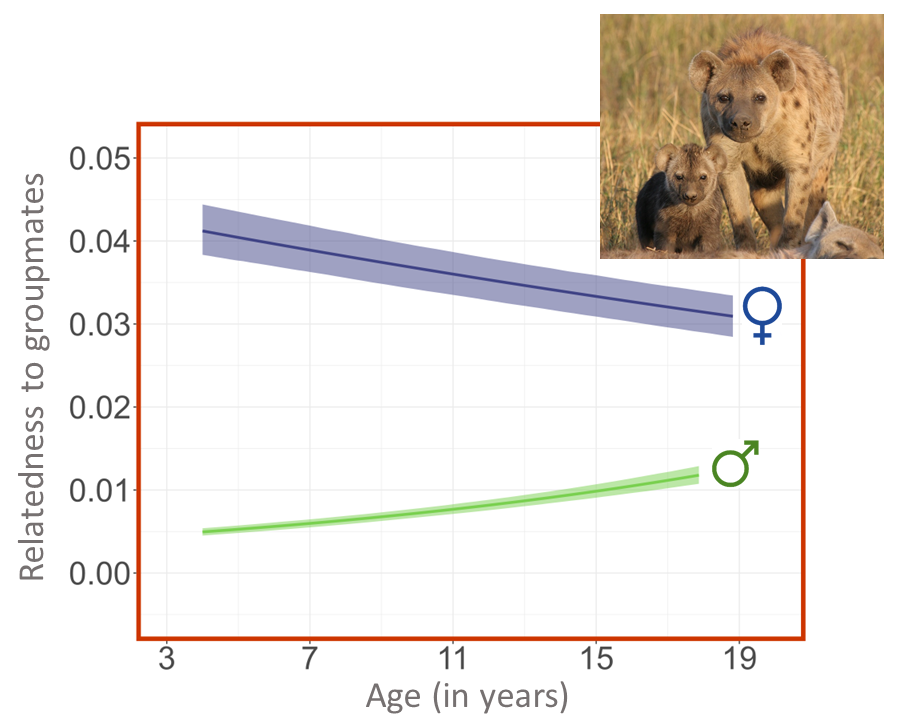

In spotted hyenas, males should become more willing to help others as they age. We found that the number of close kin increases for male hyenas but decreased for females. This pattern was largely shaped by the fact that dispersal is strongly male biased in spotted hyenas: most males leave their natal group after reaching sexual maturity and establish themselves as immigrants in other clans whereas the daughters remain in their birth clan all their life. Females therefore live among fewer close kin as they get older, because their mother and older sisters and aunts eventually die. In contrast, males have no or few kin upon immigration into their new clan but their numbers increase over time, as males sire more and more daughters (that remain in the clan). The distinct kinship dynamics in male and female hyenas predicts that males should be more willing to help other group members as they age while females should become more selfish. More detailed investigation of hyena behaviour is needed to assess if this in fact is the case. So stay tuned!

Original publication

Ellis S, Johnstone RA, Cant MA, Franks DE, Weiss MN, Alberts SC, Balcomb KS, Benton CH, Brent LJN, Crockford C, Davidian E, Delahay RJ, Ellifrit DK, Höner OP, Meniri M, McDonald RA, Nichols HJ, Thompson FJ, Vigilant L, Wittig RM, Croft DP (2022) Patterns and consequences of age-linked change in local relatedness in animal societies. Nature Ecology & Evolution.

Further information

Davidian E, Courtiol A, Wachter B, Hofer H, Höner OP (2016) Why do some males choose to breed at home when most other males disperse? Science Advances 2 e1501236.

Höner OP, Wachter B, East ML, Streich WJ, Wilhelm K, Burke T, Hofer H (2007) Female mate-choice drives the evolution of male-biased dispersal in a social mammal. Nature 448:798-801.

Vullioud C*, Davidian E*, Wachter B, Rousset F, Courtiol A*, Höner OP* (2019) Social support drives female dominance in the spotted hyaena. Nature Ecology & Evolution 3:71-76. *contributed equally